The True Origins of Saint Valentine’s Day

By: Wendy Brinker

Posted by: Magickal Winds

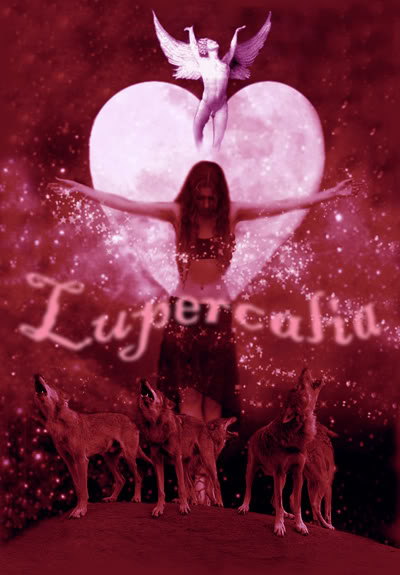

Lupercalia is uniquely Roman, but even the Romans of the first century were at a loss to explain exactly which deity or deities were being exalted. It harkens back to the days when Rome was nothing more than a few shepherds living on a hill known as Palantine and was surrounded by wilderness teeming with wolves.

Lupercus, protector of flocks against wolves, is a likely candidate; the word lupus is Latin for wolf, or perhaps Faunus, the god of agriculture and shepherds. Others suggest it was Rumina, the goddess whose temple stood near the fig tree under which the she-wolf suckled Romulus and Remus. There is no question about Lupercalia’s importance. Records indicate that Mark Antony was master of the Luperci College of Priests. He chose the Lupercalia festival of the year 44BC as the proper time to offer the crown to Julius Caesar.

According to legend, the story of Romulus and Remus begins with their grandfather Numitor, king of the ancient Italian city of Alba Longa. He was ousted by his brother Amulius. Numitor’s daughter, Rhea Silvia, was made a Vestal Virgin by Amulius and forbidden to marry since her children would be rightful heir to the throne. Mars, the god of war, fell in love with her and she gave birth to twin sons.

Fearing that the boys would grow up and seek revenge, Amulius had them placed in a basket and thrown into the freezing flooded waters of the River Tiber. When the waters receded, the basket came ashore on Palantine Hill. They were found by a she-wolf who, instead of killing them, nurtured and nourished them with her milk. A woodpecker, also sacred to Mars, brought them food as well.

The twins were later found by Faustulus, the king’s shepherd. He and his wife adopted and named them Romulus and Remus. They grew up to be bold, strong young men, and eventually led a band of shepherds in an uprising against Amulius, killing him and rightfully restoring the kingdom to their grandfather.

Deciding to found a town of their own, Romulus and Remus chose the sacred place where the she-wolf had nursed them. Romulus began to build walls on Palatine Hill, but Remus laughed because they were so low. Remus mockingly jumped over them, and in a fit of rage, Romulus killed his brother. Romulus continued the building of the new city, naming it Roma after himself.

February occurred later on the ancient Roman calendar than it does today so Lupercalia was held in the spring and regarded as a festival of purification and fertility. Each year on February 15, the Luperci priests gathered on Palantine Hill at the cave of Lupercal. Vestal virgins brought sacred cakes made from the first ears of last year’s grain harvest to the fig tree. Two naked young men, assisted by the Vestals, sacrificed a dog and a goat at the site. The blood was smeared on the foreheads of the young men and then wiped away with wool dipped in milk.

The youths then donned loincloths made from the skin of the goat and led groups of priests around the pomarium, the sacred boundary of the ancient city, and around the base of the hills of Rome. The occasion was happy and festive. As they ran about the city, the young men lightly struck women along the way with strips of the goat hide. It is from these implements of purification, or februa, that the month of February gets its name. This act supposedly provided purification from curses, bad luck, and infertility.

Long after Palentine HIll became the seat of the powerful city, state and empire of Rome, the Lupercalia festival lived on. Roman armies took the Lupercalia customs with them as they invaded France and Britain. One of these was a lottery where the names of available maidens were placed in a box and drawn out by the young men. Each man accepted the girl whose name he drew as his love – for the duration of the festival, or sometimes longer.

As Christianity began to slowly and systematically dismantle the pagan pantheons, it frequently replaced the festivals of the pagan gods with more ecumenical celebrations. It was easier to convert the local population if they could continue to celebrate on the same days… they would just be instructed to celebrate different people and ideologies.

Lupercalia, with its lover lottery, had no place in the new Christian order. In the year 496 AD, Pope Gelasius did away with the festival of Lupercalia, citing that it was pagan and immoral. He chose Valentine as the patron saint of lovers, who would be honored at the new festival on the fourteenth of every February. The church decided to come up with its own lottery and so the feast of St. Valentine featured a lottery of Saints. One would pull the name of a saint out of a box, and for the following year, study and attempt to emulate that saint.

Confusion surrounds St Valentine’s exact identity. At least three Saint Valentines are mentioned in the early martyrologies under the date of February 14th. One is described as a priest in Rome, another as a Bishop of Interamna, now Terni in Italy, and the other lived and died in Africa.

The Bishop of Interamna is most widely accepted as the basis of the modern saint. He was an early Christian martyr who lived in northern Italy in the third century and was put to death on February 14th around 270 AD by the orders of Emperor Claudius II for disobeying the ban on Christianity. However, most scholars believe Valentine of Terni and the priest Valentine of Rome were the same person.

Claudius’ Rome was an extremely dangerous place to be Christian. Valentine not only chose to be a priest, but was believed to have been a leader of the Christian underground movement. Many priests were caught, one by one and imprisoned and martyred. Valentine supposedly continued to preach the word after he was imprisoned, witnessing to the prisoners and guards.

One story tells that he was able to cure a guard’s daughter of blindness. When word got back to Claudius, he was furious and ordered Valentine’s brutal execution – beaten by clubs until dead, and then beheaded. While he was waiting for the soldiers to come and drag him away, Valentine composed a note to the girl telling her that he loved her. He signed it simply, “From Your Valentine.” The execution was carried out on February 14th.

Another legend touts of a well loved priest called Valentine living under the rule of Emperor Claudius II. Rome was constantly engaged in war. Year after year, Claudius drafted male citizens into battle to defend and expand the Roman Empire. Many Romans were unwilling to go. Married men did not want to leave their families. Younger men did not wish to leave their sweethearts. Claudius ordered a moratorium on all marriages and that all engagements must be broken off immediately.

Valentine disagreed with his emperor. When a young couple came to the temple seeking to be married, Valentine secretly obliged them. Others came and were quietly married. Valentine became the friend of lovers in every district of Rome. But such secrets could not be kept for long. Valentine was dragged from the temple. Many pleaded with Claudius for Valentine’s release but to no avail, and in a dungeon, Valentine languished and died. His devoted friends are said to have buried him in the church of St. Praxedes on the 14th of February.

The Feast of St. Valentine and the saint lottery lasted for a couple hundred years, but the church just couldn’t rid the people’s memory of Lupercalia. In time, the church gave up on Valentine all together. Protestant churches don’t recognize saints at all, and very few Catholic churches choose to celebrate or observe the life of St. Valentine on a ‘Valentine’s Sunday’. The lottery finally returned to coupling eligible singles in the 15th century. The church attempted to revive the saint lottery once again in the 16th century, but it never caught on.

During the medieval days of chivalry, the single’s lottery was very popular. The names of English maidens and bachelors were put into a box and drawn out in pairs. The couple exchanged gifts and the girl became the man’s valentine for a year. He wore her name on his sleeve and it was his bounded duty to attend and protect her. The ancient custom of drawing names on the 14th of February was considered a good omen for love.

Arguably, you could say the very first valentine cards were the slips of paper bearing names of maidens the early Romans first drew. Or perhaps the note Valentine passed from his death cell. The first modern valentine cards are attributed to the young French Duke of Orleans. He was captured in battle and held prisoner in the Tower of London for many years. He was most prolific during his stay and wrote countless love poems to his wife. About sixty of them remain. They are among the royal papers in the British Museum.

By the 17th century, handmade cards had become quite elaborate. Pre-fabricated ones were only for those with means. In 1797, a British publisher issued The Young Man’s Valentine Writer, which contained suggested sentimental verses for the young lover suffering from writer’s block. Printers began producing a limited number of cards with verses and sketches, called “mechanical valentines,” and a reduction in postal rates in the next century ushered in the practice of mailing valentines.

This made it possible to exchange cards anonymously and suddenly, racy, sexually suggestive verses started appearing in great numbers, causing quite a stir among prudish Victorians. The number of obscene valentines caused several countries to ban the practice of exchanging cards. Late in the nineteenth century, the post office in Chicago rejected some twenty-five thousand cards on the grounds that they were not fit to be carried through the U.S. mail.

The first American publisher of valentines was printer and artist Esther Howland. Her elaborate lace cards of the 1870’s cost from five to ten dollars, some as much as thirty-five dollars. Since then, the valentine card business has flourished. With the exception of Christmas, Americans exchange more cards on Valentine’s Day than at any other time of year.

Chocolate entered the Valentine’s Day ritual relatively late. The Conquistadors brought chocolate to Spain in 1528 and while they knew how to make cocoa from the beans, it wasn’t until 1847 that Fry & Sons discovered a way to make chocolate edible. Twenty years later, the Cadbury Brothers discovered how to make chocolate even smoother and sweeter. By 1868, the Cadburys were turning out the first boxed chocolate. They were elaborate boxes made of velvet and mirrors and retained their value as trinket-boxes after the chocolate was gone. Richard Cadbury created the first heart-shaped Valentine’s Day box of candy sometime around 1870.

By: Wendy Brinker

Posted by: Magickal Winds

Posted in Origins and tagged February 14, Lupercalia, Magickal Winds, pagan, St. Valentine's Day, Valentine's Day, Wicca by admin with 1 comment.